Group Evaluation of Reading Eggs

Introduction: What is Reading Eggs?

Reading eggs is an educational online tool designed to develop children’s reading skills in a fun and engaging way. This gamified reading app focuses on phonemic awareness, vocabulary development, and reading comprehension for children ages 2-13.

A brief walk-through of the app/how it motivates appropriately aged children:

Step 1:

Beginning with a placement test allows students to enter at a level that is best suited for them. This is a key feature as it avoids initial boredom/discouragement. When students begin at a level that they can be successful in, it provides them with a sense of confidence that “is tied intimately to success” (Gurthrie, 2011, p.178,), whereas, “students who struggle begin to doubt their abilities” (p.179) and therefore “report declines in self-efficacy for reading” (p.193).

Step 2:

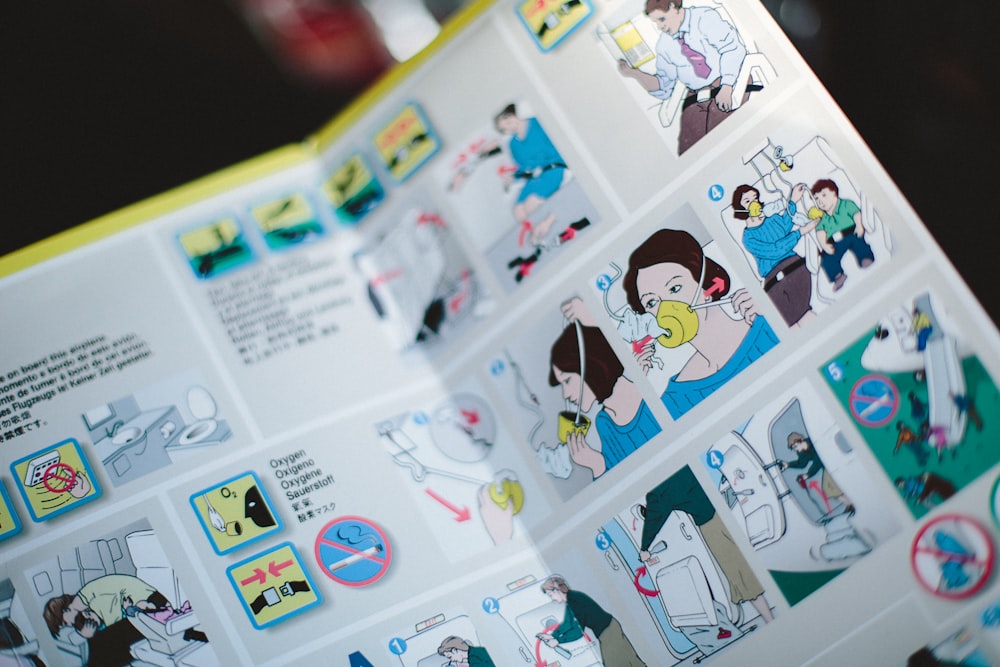

Reading eggs is a self-paced learning app which allows students to pause, re-do, or proceed as they please (interactivity effect). This sense of self-direction has been proven to increase a child’s motivation to read (Gurthrie, 2011, p.180). Furthermore, each activity is designed as a game and the information that is being taught is reiterated multiple times throughout each game to increase retention (redundancy principle).

- In this example, players are asked to tap all the rocket ships that have the word “go” on them as they fly through the air. This design is engaging for young learners (as it simply feels like a game).

Step 3:

Not only does this app have games/activities to increase reading skills, but it also offers other engaging materials such as a reading library. Students choose books that interest them (which increases intrinsic motivation). Although rewards are initially useful when introducing reading to children, “extrinsic rewards do not motivate reading achievement in the long term” (Gurthrie, 2011, p.178), and therefore, providing children with choice and topics that are relevant to their lives/interests increases intrinsic motivation, which in turn increases retention (p.183-188).

Step 4:

Parents can track their child’s progress regularly on the app and through periodic email updates. Additionally, Reading eggs has a ‘teacher dashboard’ to keep track of each student’s progress (which fosters the integration of reading eggs in a classroom and/or at home reading program).

Step 5:

Reading eggs rewards students for their progress. While extrinsic motivation may not be the solution long term, rewards get children excited about an activity and serve as a great “jump start” to get students interested in reading (Gurthrie, 2011, p.178).

Case Study:

While reading eggs is designed to feel entirely like a game, research shows that the app significantly improves overall reading skills. In 2017, Latisha Lowery conducted a study to see how effective regular use of Reading Eggs was on student’s reading proficiency levels. The study was done in a rural community where 32% of the students lacked phonetic awareness and/or comprehension skills (Lowery, 2017). The school decided to introduce reading eggs as part of their intervention program (in combination with teacher support). The students who participated in this study were in grade two, chosen at random, and were split into two test groups. Class A would each spend 30 minutes on reading eggs a day, complete with weekly reports tracking their progress, and had teacher instruction along the way. The second group, class B, did not use reading eggs and solely relied on teacher instruction. The results showed that Class A demonstrated growth and the amount of students reading below grade level decreased by 19%, and the amount of students reading above grade level increased by 6% (Lowery, 2017). It should be noted, however, that while the use of this app was clearly effective, Reading Eggs should not supplement teacher instruction entirely. Namely, it should be used as a tool in the classroom to help improve both phonetic and comprehension skills. The school continues to use reading eggs as part of their intervention program.

A Teacher Review of Reading Eggs – Barbara Petersen’s First Impressions

- After walking through the app with Barbara Petersen (a Vancouver Island Kindergarten-Grade 3 teacher), this what she had to say:

- Well organized and easy to use

- Can be a bit cartoonish (good for younger learners)

- Repetitive, but in a positive way, that would hold the child’s interest

- Likes the practicing typing aspect

- Impressed with the use of music

- Impressed with the pronunciations of phonetic sounds

- After walking through the app, Barbara says she would feel comfortable recommending this app to Kindergarten and Grade One students. She also believes it is a fun and engaging way for students to practice reading at home. She also states it would be a good addition to the at-home aspect of a reading program.

A Parent Review of Reading Eggs:

Which Multimedia Principles does Reading Eggs Contain?

When evaluating Reading Eggs based on the Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, it is evident that it is a useful educational tool to incorporate in the classroom as it follows many of the multimedia principles discussed in the handbook.

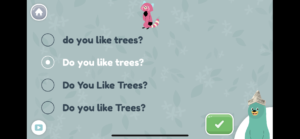

Feedback Principle:

Reading Eggs provides users with immediate “correct” or “incorrect” feedback. The app also does a good job of summarizing the information and learning that the learner has completed at the end of the lesson which guides the user to understand the overall important aspects of the lesson. This being an example of explanatory feedback whereas the program “provides the learner with a principle-based explanation of why his or her answer was correct or incorrect” (Mayer, 2014, p.450).

Redundancy Principle:

The app provides a variety of learning games and activities for each lesson which allows students to obtain identical information in diverse ways (Mayer, 2014, p. 248).

Multimedia Principle:

Throughout the app, there is the use of images, words, text, music, and auditory instructions that are used to teach concepts to and engage the learner (Mayer, 2014, p.175).

Coherence Principle:

A limitation of this app is its neglect of the coherence principle. The coherence principle states that “people learn more deeply from a multimedia message when extraneous material is excluded rather than included” (Mayer, 2014, p. 279). However, as the issue with disobeying this principle is that added information has the potential to hinder one’s learning rather than nurturing it (Andrade, 2013). Reading Eggs does, however, have the element of “fun” and “fantasy” which in theory and practice, is shown to have positive effects on learning by making the material and educational activities more intrinsically moving for students (Parker, 1992).

How Reading Eggs Supports Multimedia Learning at Home

When it comes to literacy, school is not the only place students can learn important skills. Especially in their early year’s students need access to tools and activities that can help them become better readers and writers in the future. It is important that caregivers encourage activities that help students learn literacy skills at home as studies have found that “home literacy activities such as writing, storybook reading, and identifying environmental print positively influences emergent literacy.” (Neumann, 2016) In today’s evolving world, technology is more prevalent than ever, meaning many of the literacy activities students will take part in are run through apps. This is where Reading Eggs comes in, through engaging activities students to build their literacy skills at home, something we now know is particularly important. And using technology to build literacy skills will only aid and not hinder students’ literacy when not using technology as “children were observed to transfer their developing knowledge of letter and sound relationships and word spacing between these tools. This illustrates that young children are capable of using digital and non-digital tools for literacy learning.” (Neumann, 2016)

References:

Andrade, G. (2013). Coherence Principle Analysis. GregAndradeEdTechLearningLog.

https://gregandradedesign.wordpress.com/edtech-513-projects/coherence-principle-analysis/

Guthrie, John T. (2011).Best Practices in Motivating Students to Read. Best Practices in Literacy Instruction.(4th ed.), p.177 – 194.

Lowery, Latisha D. (2017) Effects of Reading Eggs on Reading Proficiency Levels. University of South Carolina Scholar Commons. Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5160&context=etd

Mayer, R. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139547369

Neumann, M. M. (2016). Young children’s Use of Touch Screen Tablets for Writing and Reading at Home: Relationships with Emergent Literacy. Computers & Education. 97, 61-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.02.013

Parker, L. (1992). Effects of fantasy contexts on children’s learning and motivation: Making learning more fun. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. US: American Psychological Association, 62(40), 625-653.

Recent Comments